You may think a career is an old fashioned concept out of the 80s which could be safely ignored. I sure used to… I thought a career was for banking professionals in suits, not for me! I was young and cool and wanted to work for a living, of course, but I couldn’t care less about climbing up the career ladder. Well, I changed my mind.

I’m not saying that a career should be everyone’s focus at every point in one’s life. Just having a job is a totally legit choice. But if you want to to have a career, in the sense of progressing throughout your work life, expanding your horizons and opportunities for personal and professional impact, here’s a list of 8 things to avoid doing.

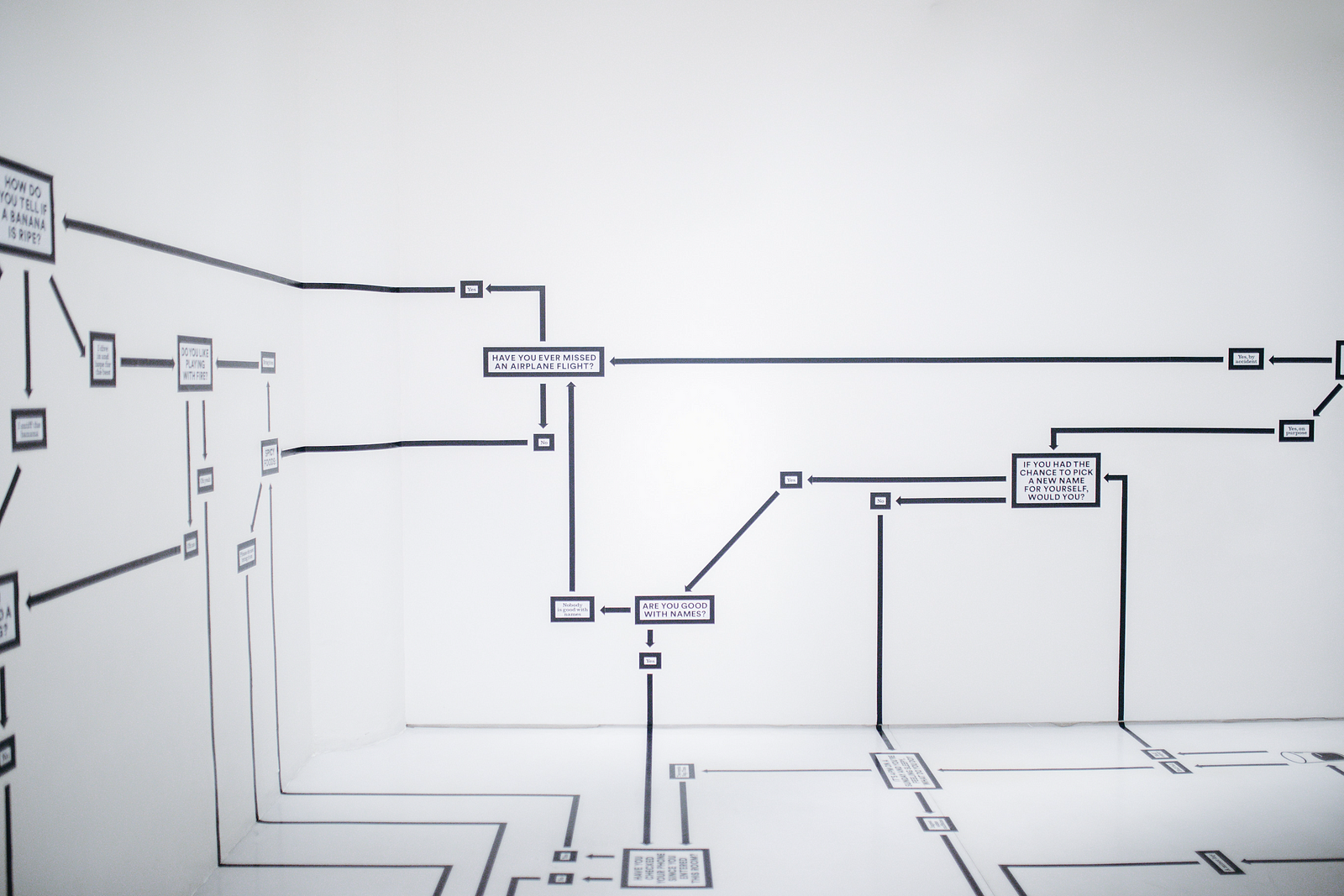

1. Don’t plan ahead

It’s easy to just flow with opportunities that present themselves, go on a few interviews, take the best offer you get, stay for a few years, rinse, repeat. That will probably work for getting small raises and some variety in your daily work.

But if you want a career you should have a short, mid and long term plan (2, 5, 10 years ahead) and be intentional about reaching goals that will advance you in the right direction. Imagine what you want to be “when you grow up”, give yourself room to experiment and try different things in order to achieve that long term vision, but always keep your eyes on the ball. Remember that you can always change your plans according to your shifting wants and needs, but if you don’t have one at all it’s unlikely you will be very effective in getting much of anywhere.

Sometimes “leaning out” is perfectly fine, if you want to focus on other things besides work for a while, but it’s important to be intentional about it. Otherwise you’ll find yourself looking back and seeing wasted time instead of time well spent doing other things.

Whichever path you choose, put your 2, 5, 10 years plan in writing so you can reflect on it every year or so and adjust your plan or your goals according to the progress you made or what’s going on in your life.

Once, not so long ago, I set a 7 year goal and ended up achieving it in less than 2 years. That was fun, exciting and encouraging and I could set my sights on the next goal!

2. Do the work and wait for recognition to come

This is a common misconception — we assume that if we do good work we’ll get recognized and promoted for it. It makes sense on the surface, right? Our work will speak for us, we shouldn’t have to broadcast it, it’s self-evident.

Unfortunately, that’s not how things work. Assuming that (hopefully) competence is a prerequisite for promotion, and even under the best of performance review systems, you’ll still have to help your manager see what you’ve achieved. In fact, sometimes our best work is utterly invisible — if the project you worked on succeeded without any major outages or errors, it might be less visible and therefore less appreciated than a project with major setbacks and failures which created a lot of “noise”.

Try to get comfortable telling people about your successes. Even sharing failures and how you overcame them is a powerful message. If you find this hard to do, try to craft your messages in a way that benefit your readers/listeners — frame it as a “lesson learned” or as a team success story (without giving all the credit to the team). You won’t look like you’re bragging, but will get the visibility you need.

If you can’t manage that, please try again. But if you just can’t bring yourself to do it — another useful strategy is to form a group of allies who praise each other in public settings. You may think it’s obvious what you’re doing, but it’s not, people won’t notice. And if they do — who cares, your message is out anyway.

I recommend keeping a weekly log of things you did at work, good or bad. I’ve been doing it for a while and it helps me keep a semi-objective record of what I’ve achieved and all the data points I need for my self-review and 1:1 conversations with my manager. I also use it for sprint retros, highlights/lowlights of work with other team members for their 360 reviews etc. There’s no way I would be able to remember enough to give quality feedback for myself or others without it.

On top of the effort to make your work visible, remember to ask for what you want. Even the best of managers might not be aware you’re interested in. Others might find it easier to only react only when specifically asked or faced with an ultimatum. Don’t let them get away with that. Tell whoever’s willing to listen that you want a promotion or a raise. Share with your manager that you feel you’d like some recognition. If you don’t get what you asked for — at least you’ll know you’ve done your best (and maybe it’s time to move on to a manager who will recognize your worth).

3. All or nothing outlook

Sometimes you’ll look at your colleagues and think they’re just so much smarter than you or something about their circumstances enables them to work harder, longer hours or with less interruptions (e.g. if you have kids and they don’t). There’s no way you can win against them, they’ll always be more successful than you, so what’s the point of trying?

I fell into this kind of thinking after having kids. I wanted to spend time with them and I figured I couldn’t “win” over single or childless colleagues, so I should just “give up”. I didn’t think of it that way exactly, but for the most part — that’s what I did in practice.

I’m not going to sugar-coat this: yes, you probably can’t “win”. There will always be people who are smarter than you and have more time, less responsibilities, more ambition… But a career is not a zero-sum game. Just because other people will advance faster than you at a certain times in your/their life, doesn’t mean you can’t advance at all. Don’t give up, adjust your expectations to what you can achieve and don’t compare yourself to others (too much…), it will probably just discourage you. In the long term it won’t matter if you got a promotion a year or two later. However, it might make a huge difference if you wait 10 years because you think someone else’s success prevent you from achieving anything yourself.

4. Undersell yourself

This may sound a bit like #2 in this list, but it’s subtly different. #2 is about doing good work, realizing it’s good work, just not telling anybody. This one is about your narrative. You may not realize that your work is good or just not know how to phrase it, but the effect is the same: people will get the wrong impression of you.

Here’s a story:

I worked mostly alone for 6 years, with a few freelance developers and an architect helping me. I had to do everything myself, including product work. After a few years the company was sold to a larger company, and I decided it was time to move on.

Here’s another story:

For 6 years I lead the development of a successful product, enlisting the help of freelance developers and consulting with a software architect I worked closely with. I worked directly with senior staff, provided valuable product input and coordinated the design work. Partly due to the excellent technical quality of the product, the company was sold to a giant European corporation. I felt I had spent my time there well, but it was time to move on to new challenges.

Both of these stories are (my) true stories. But the first one is underselling what I actually did. It’s the story of a passive lone wolf (which I am not). The second one is the better version, highlighting my strengths and impact.

In my experience mentoring, I’ve found many who take the first approach when constructing their story (I know I’ve made this mistake). They just don’t understand how it sounds.

Don’t underestimate the impact of constructing a powerful narrative. If you’re job searching, get a few people to listen to your 3–5 minute “tell me about yourself” pitch and listen to their feedback about how you come across. Same for the “who am I and what am I looking for” section of your CV or cover letter.

In fact, it’s best if you do the same for all the “soft” part of the interviewing process. The same series of events can be told in a way that portrays you as resentful or as proactive, as a failure or as a person who learns from their mistakes. You should take the time to prepare for soft skills interviews by writing down your stories and bouncing them off listeners, rewriting them to convey the best version of yourself. Remember, this isn’t about bending the truth, it’s about building your narrative in a way that serves you well.

If you’re not searching for a job right now, it’s still worth while to think about your story and how it fits in to your self image and long term goals. Maybe you don’t appreciate yourself enough and that’s holding you back.

5. Who needs a network

Networking may sound a bit artificial, like going to a bunch of events and engaging in worthless small talk just to pass around antiquated business cards which will be lost seconds after leaving the event. If that’s how you’re doing it, you’re doing it wrong and yes, it’s pretty worthless.

However, building an actual professional network is far from worthless. Having a strong network can provide you with access to knowledge, guidance and opportunities hard to come by in other ways. Whether you’re looking for a job or for advice, a co-founder or other support, there’s bound to be someone in your network who can help, if not themselves — by connecting you to someone who can. Sometimes they’re the one’s looking for jobs, advice etc. and you can be the one to provide value. Even if there’s no immediate payoff (like finding the right person for an open position), in the long run you’ll probably benefit from that relationship in one way or another. And if not? At least you did some good.

The stronger your network is, the more people you know, the likelier it is that you’ll be able to find what you need, when you need it. In a way, creating a network is like building luck into your life.

While building a network can happen organically if you happen to go to the “right” school and worked in the “right” places, it’s better if you put some conscious effort into it, particularly if you’re less privileged in that respect. Going to or even organizing meetups and network events is one way, building an online presence is another. Make the most of the connections you make while working. Try to make a meaningful connection, don’t just stick to superficial small talk, that won’t leave a lasting impression. Approach people you find interesting. Start by thinking of what you can do for them, not what they can do for you. The rest will come with time.

6. Blame others for things you can control

You couldn’t have known. You didn’t get the right requirements. The other group didn’t come through with what you needed. You didn’t get that promotion because you were given low impact tasks. You didn’t get a raise because your boss doesn’t like you. It’s not your fault.

In any failure there is something that could have been done to prevent it. Perhaps you couldn’t have avoided the failure altogether, but there are probably things you could have done differently. And in retrospective, there are things to learn from it in order to avoid the next failure. Assigning blame might feel good, but it erodes trust and won’t help you grow.

Instead, embrace failure. Instead of deflecting, think about ways you could have done something differently to achieve a different outcome: Clarified expectations, communicated better, taken initiative etc. You will not only grow personally, but you will also gain credibility. People love to hear others admit failure and share lessons learned, it’s far more sympathetic and interesting to hear someone taking responsibility for their actions than a rant about how everyone else is just terrible.

I remember once I did a major refactor of some enormous amount of duplicated code, and I missed one “if” which caused a semi-serious performance degradation. In some meeting much later where we were discussing performance in general, that example was brought up without mentioning my name, probably in order not to embarrass me. I had no problem admitting I had made a mistake and shared the story how it happened and how I investigated, found, and fixed the problem, for everyone’s benefit. I’m sure no one thinks less of me because I shared that story.

The end of the saga is someone else was doing some refactoring in that area and I saw a chance to get rid of that “if” entirely, if I hadn’t known about the risk due to my previous mistake — I wouldn’t have even noticed that chance to make our code base better. All in all, a win (and sorry to anyone who had to wait an extra 200 ms loading that page for a couple of days).

7. Blame yourself for things you can’t control

You couldn’t have known. You didn’t get the right requirements. The other group didn’t come through with what you needed. You didn’t get that promotion because you were given low impact tasks. You didn’t get a raise because your boss doesn’t like you. It’s not your fault.

I know this is exactly the same list as #6, the thing is — sometimes it’s not your fault. Sometimes you are really in a toxic environment which undervalues and even sabotages you. If you’re the type of person that always tries to learn and grow from failure, you might find yourself staying in a work environment which is doing nothing for you and even hurting you. It’s sometimes hard to tell the difference. But if you do the work and aren’t getting anywhere, and if you get a sinking feeling in your stomach every time you go to work, perhaps there’s nothing more you can do and it’s time to leave.

There are enough toxic environments to go around, but I believe that women and other URMs encounter this type of dilemma more often. When there are subtle, hard to pinpoint behaviors, it’s easy to blame yourself and try to work through them, instead of realizing it’s something systemic and it’s truly not your fault. If you’re being passed over for promotion in spite of you being more accomplished than a male colleague, if you’re being talked over in meetings, called “not technical enough” and other biased incidents, it’s quite possible you can’t win. You’ll probably encounter some of it anywhere you go, so try and do what you can to improve the situation, but whatever you do, be aware: it’s not your fault.

8. Get comfortable

When you start out in a new place, you’re eager to prove yourself. It’s hard, you have to learn everything, get to know everyone, build a reputation. After a while, things get easier. You understand the processes, know who’s who, gain professional knowledge and stature. It’s nice to feel that way, the pressure is off for a bit.

There’s nothing wrong with being a little comfortable, work shouldn’t be a constant struggle. But if you’re using comfortable to describe your work, maybe it’s time to shake things up a bit. You wouldn’t want to lose all the progress you made by staying in the same place (professionally) for too long.

Constant searching for “the next thing” is probably not the best strategy. It’s stressful and you’ll be seen as unstable or unreliable, but once every one or two years is probably a good cadence for checking what your next challenge should be, inside or outside the organization you already work for. You might discover you are under paid or “stuck” professionally, and you’d be better off knowing earlier rather than later, when it might be harder to fix.

I hope I have done my bit to help you on your path to an amazing career. Check back in a few years, I might have a few more mistakes to add to this list… But you can bet I won’t let that stop me, and you shouldn’t either.